Parent | Coach | Athlete

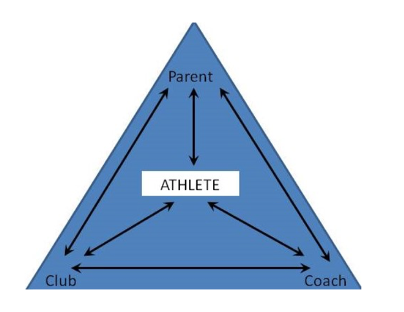

The following piece provides a general outline of the triadic relationship between parent, coach and athlete from a youth and secondary school sports perspective focusing on the function of effective communication for optimum athletic success focusing mainly on one piece of research by Holden et al (2015).

The work by Holden et al (2015) states that every situation, athlete, coach, and parent is different, but the significance of the cohesiveness within the athletic triangle and its effect on athletic success is universal.

For children who choose to participate in sport, their parents should be educated on their roles in their child’s development. This should include the parent’s role in the youth sport triad (coach, parent, and athlete). This process ought to specify the behavioural expectations of the parents of a young athlete.

The fundamental aim for parents and coaches is to have positive relationships with one another. However, this is not always the case. Knowing and understanding one another’s expectations will help to develop a foundation for positive interactions of the individuals within the athletic triad which is crucial for improving the quality of the sporting experience for the everyone involved.

Each section of these relationships includes the roles, responsibilities, and behaviours necessary for the sport experience to be successful, whatever success looks like for that person as it is different for everyone. For example, it is expected that coaches should provide an environment that is physically and emotionally safe for the players, whilst providing a developmentally appropriate sporting experience, and should behave in line with the code of ethics for coaches.

It is expected that players follow the coach’s instructions, display good sportsmanship behaviours, attend all training sessions and matches/events and should give their best effort in both.

Parents should follow the parents’ code of behaviour, which some clubs have written (e.g. not shouting or criticising players, management, or officials), show up to as many of the athlete’s games as possible, and make sure the player has transportation to and from training and games (when necessary).

Parents should provide kit and safety equipment (if needed) but should refrain from emphasising winning over the process of skill and the development of their child. Additionally, parents should encourage sport enjoyment, which would encourage amotivation.

Coaches’ Expectations of Parents:

There is a lot literature written around the coaches’ expectations of parents Erickson (2004), and a coach has the expectations (listed below) of their players’ parents:

a) Drive them back and forth from training or games.

b) Help the kids to learn the elementary fundamentals and back them up at home.

c) Allow their kids to practice assorted repetitive skills at home.

d) Be punctual to training and matches.

e) Display positive behaviours at training and games.

f) Alert the coach if there any health or medical problems.

Furthermore, there are some expectations for appropriate parental behaviour when at competitions:

a) Do stay in the area for spectators during an event.

b) Do not interfere with the coach for at least 24 hours or wait until the following day before speaking with the coach.

c) Do express attention and encouragement to the children.

d) Do help out when a coach or referee asks.

e) Under any circumstance, do not express any offensive comments to anyone (players, parents, coaches of either team or officials).

The more effective coaches have clear and consistent messages when interacting and imposing their guidelines around parent behaviour. More often or not coaches have parents sign an agreement whereby they state that they understand and will respect the rules of behaviour. This is only one factor of an effective athletic triad. Also, coaches need to be aware of the parent’s expectations for a “model coach.”

Parents’ Expectations of Coaches

Erickson (2004) noted these general expectations that parents have for their kids’ coaches when coaching them at the youth and secondary school ages:

a) Training should be fun and focus on the basic skills.

b) The athletes should be treated in fair and consistent manner.

c) Coaches will not use vulgar language or misuse alcohol.

d) Criticism will be directed on skill correction and not the child.

e) Coaches will speak frequently with parents about timetables, advice around home practice, kit, etc.

f) Coaches will assist the athletes to grow and mature in individual success, self-worth, teamwork, and team support.

g) Coaches will emphasis on doing the best the athlete can, not just winning. Additionally, parents should want their kids to experience an enjoyable sporting time.

For youth players to really enjoy their sporting experience however, parents and coaches need to continue to be very mindful of the reasons why young players participate in sport.

It has been documented throughout extensive literature that the majority of youth athletes partake in sports for only one reason and that is to have fun. Whilst it is perfectly customary and normal for parents to have their own beliefs about a coach, they should be focused around the fact that sports for their kids should be fun for the athletes.

Parents and coaches who are on the same wavelength with regards to the child’s well-being and development create an excellent foundation towards a youth athletes’ success. One basketball coach from Las Vegas, Jerry Tarkanian, said, “I want my players to understand that I’ll do everything I can for them with their problems away from the basketball court. But they also have to understand that I need their help solving my problems on the basketball court” (Warren, 1997).

Consequently, a successful athletic experience does rely on the coach-player relationship and this understanding of both parties’ expectations and aspirations for sport and coaching.

Coaches’ and Players’ Expectations of Each Other

Within the triad, coaches must also classify and speak these expectations to their players and parents. Training and game expectations for players are included below:

a) They should always be a good sports person.

b) They do not show any disrespect to anyone (their team, trainers, or referees);

c) They behave like a winner even in defeat.

d) They need to be willing to work hard, learn, and enjoy themselves.

e) They need to let the coach know as soon as possible if they are going to miss a match or training because it is unfair for their teammates.

f) They should be learning skills and train at home.

A lot of coaches believe an athlete enjoys sport solely upon winning games and competition. There are players who feel this way; however, research implies sporting enjoyment is more closely connected with the climate of motivation made by the coaches compared to their win record (Cumming et al, 2007).

Young athletes take part in sport because they enjoy it, want to improve their skills and develop new ones, for excitement, to spend time with friends or to make friends and to thrive or win (Universities Study Committee, 1978).

Likewise, Pugh et al. (2000) determined subject’s (International male youth baseball players) leading motives for doing sport were enjoyment, being social, and testing their skills. Additionally, they stated their main stressors which were being shouted at by their trainers, parents/guardians, team members, and supporters. Additionally, at the end of the season the researchers said that the majority couldn’t remember last season’s record for wins and losses.

Keeping this in mind, coaches should have a think whether or not if they are creating an environment where their athletes are enjoying the sport experience and achievements (wins, life lesson learned, hard work etc.) by examining their coaching beliefs and behaviours. Coaches who are regarded as being “successful” usually have similar approaches or objectives for their season, and features of the players they have on their team.

Warren (1997) said that his coaching philosophy was to, “ensure that team membership is one of the most positive, rewarding experiences of their lives.” Bear Bryant said that he felt what truly matters is how teams are built by individuals who are so devoted to each other and have “one heartbeat.”

One key area of the team that a coach should study is the culture around the team. Some book recommendations for this would be Legacy by James M Kerr and Togetherness – How to build a Winning Team by Dr Matt Slater.

Vince Lombardi (American Football Coach) firmly believed in working hard and being relentless with regards to effort and this led his players to win in the National Football League (NFL) and gain respect from his players.

John Wooden’s (former basketball coach) approach differed slightly from Lombardi’s. Even though he also believed in hard work he also thought coaches should create clear and severe rules and consequences as it would make the younger athletes more mentally resilient and make them work harder in not just sports, but all aspects in life (Warren, 1997). He believed that making his players accountable helped to foster a culture of dedication and hard work.

Players want their coaches to appreciate their efforts and for them not get unnoticed. Most accomplished coaches do know this and apply this reinforced behaviour appropriately. Over time, and perhaps subconsciously, the players adopt the coach’s personality and hold similar values and beliefs. When this happens, it strengthens the coach-athlete relationship within this triad and unless there are any problems along the way. Unfortunately, conflicts and issues will unavoidably occur. Next will be one technique which will offer a way of reducing the possibilities of these conflicting from happening.

Top Tip: Pre-Season Meeting

When the coach recognises what the parents and players expect from the coach, they are more ready to handle any problems that appear throughout the season. A beginning of the year parents’ meeting is one of the most used approaches in team/program management which does help a great deal with preventing conflict.

This should happen within the first week. This meeting should be compulsory for team participation. Coaches have different opinions whether or not to include players within this meeting. Whatever the decision is for player attendance, one or both parents / guardians should be in attendance of the meeting.

Parent and players should receive their contracts before this meeting so they can be looked at prior attending the meeting. The head coach during the meeting should introduce all of their support staff, explain in detail their coaching philosophy, team objectives, guidelines, and policies. Furthermore, coaches should examine the player and parent expectations for games and training again and gather in the signed behavioural contracts before they leave the meeting.

The head coach should reveal training and match timetables, in addition to any other information with regards to parent or athlete behaviour. An important element to the achievement of this initial parent meeting is the organisation of the meeting by the coaches.

In theory, parents should get a copy of the programme and any extra information before this meeting takes place by email or at the start of it. Coaches should allow the parents to introduce themselves to one another and allow the meeting to maintain an order and be timely.

References

Cumming, S. P., Smoll, F. L., Smith, R. E., & Grossbard, J. R. (2007). Is winning everything? The relative contributions of motivational climate and won-lost percentages in youth sports. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 19, 322-336.

Erickson, D. (2004). Molding young athletes. Oregon, WI: Purington Press.

Holden, S. L., Forester, B. E., Keshock, C. M., & Pugh, S. F. (2015). How to Effectively Manage Coach, Parent, and Player Relationships. Sport Journal.

Pugh, S., Wolff, R., DeFrancesco, C., Gilley, W, & Heitman, R. (2000). A case study of elite male youth baseball athletes’ perception of the youth sports experience. Education, 120 (4), 773-781.

Universities Study Committee. (1978). Joint legislative Study on youth sports programs: Phase II. Agency Sponsored Sports, Institute for the Study of Youth Sports, East Lasing, Michigan.

Warren. W. E. (1997). Coaching and control. Englewood Cliff, NJ: Prentice Hall.